Deserto do Atacama, CHILE

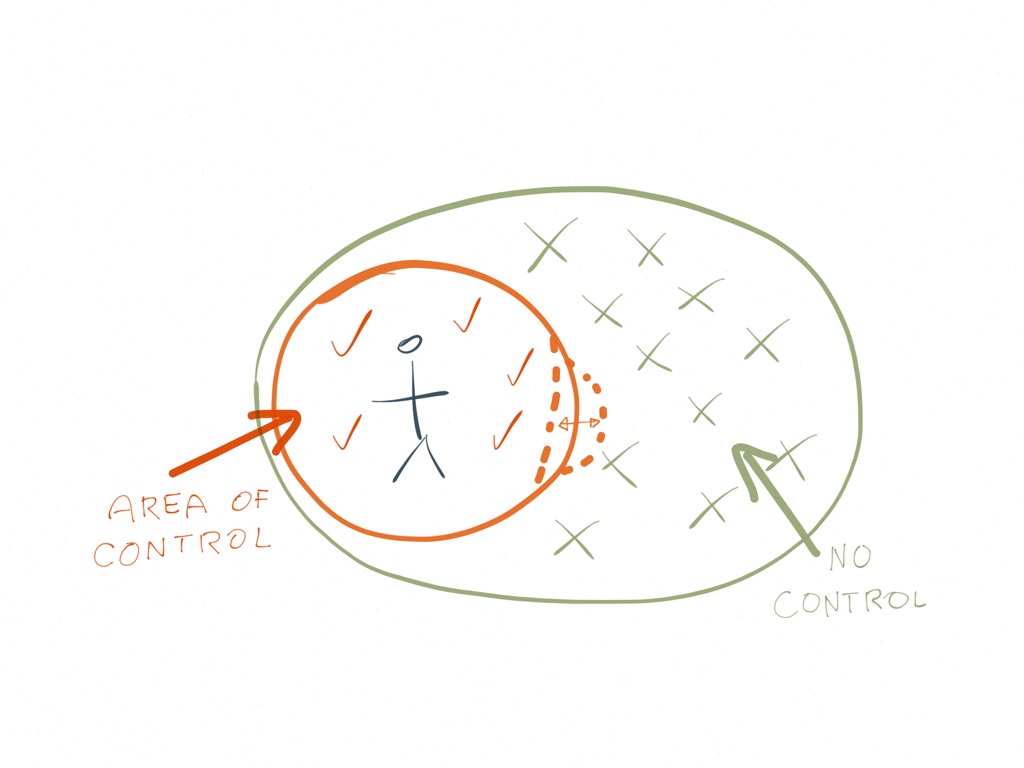

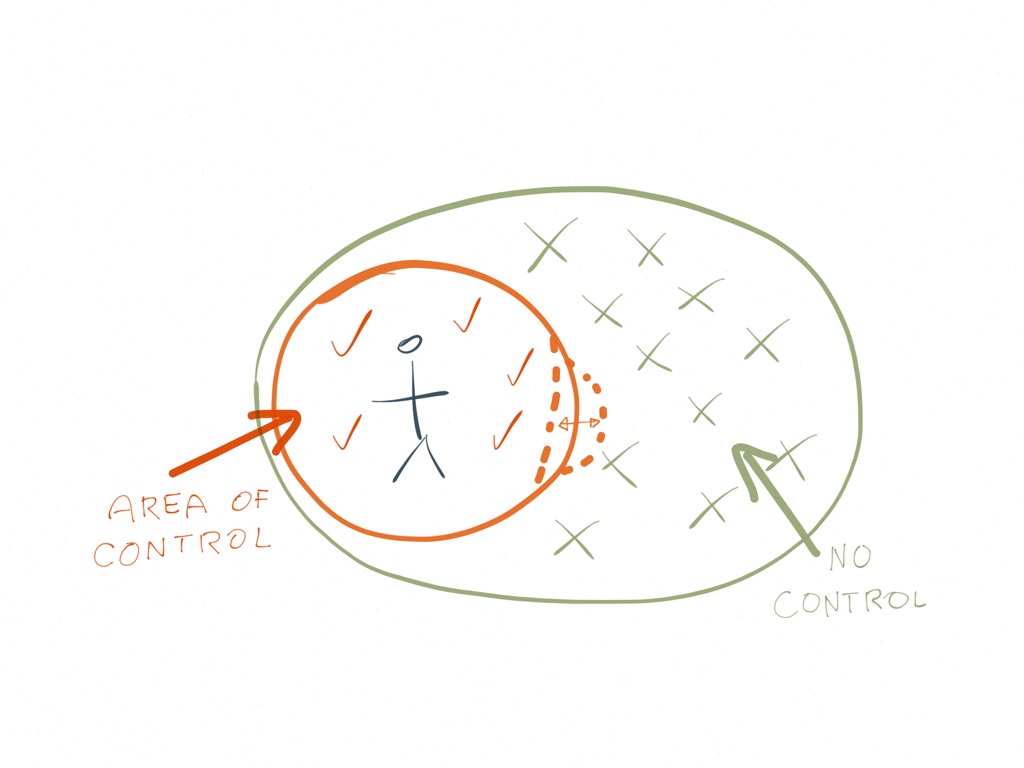

Vivemos num universo cheio de aleatoriedade e imprevistos. Parte deste mundo está dentro da nossa área de controlo: por exemplo terá escolhido o que traz hoje vestido. Outra parte, não - não lhe deram a escolher este fantástico bom tempo em finais de Outubro, nem se o seu chefe viria bem ou mal humorado.

A fronteira é flexível: alguém com perfil altamente controlador estará permanentemente a tentar lutar por conquistar mais e mais área de influência, da mesma forma que um monge tibetano cultivará aceitação, reduzindo-a. E desta tão elementar distinção, decorre uma reflexão estrutural sobre a noção de Compromisso.

Imagine que tem um café combinado com um amigo às 14h30. Uma inédita fila de espera no banco atrasa-o. Algum problema no sistema. Quando acaba finalmente de ser atendido são já 14h00 e apercebe-se que vai ser difícil, se não mesmo impossível, chegar a horas ao seu compromisso. Na melhor das hipóteses, conseguirá 14h40, talvez 14h45. O que faz?

Hipótese 1: Liga logo a avisar, perguntando se é razoável recombinar para as 14h45.

Hipótese 2: Liga só às 14h30, a dizer que está a caminho, 5 minutinhos atrasado (mentindo, portanto).

Hipótese 3: Não liga, e chega às 14h45, stressadíssimo, desfazendo-se em desculpas, alegando que algo totalmente imprevisto o fez atrasar-se.

Em qual das hipóteses existe real zelo pela promessa feita?

Esta questão é particularmente impactante em equipas de alta performance, onde o alicerce "confiança" e "fiabilidade" são valores incontornáveis. Ninguém põe em causa que há variáveis incontroláveis, mas ser responsável exige acima de tudo a imediata renegociação quando uma dessas variáveis faz perigar uma promessa, para que todos se possam reposicionar de acordo, aproveitando o seu tempo, ou até correr em auxílio se pertinente. Gestão de projetos será uma das disciplinas que melhor conhece as vantagens do "impeccable commitment": todos têm que avisar ANTES de falhar, mal se apercebem dessa possibilidade, e não com o caldo já entornado.

Sinto que estamos culturalmente a enviesar, talvez mesmo esvaziar o conceito Compromisso. Por um lado, quando descuramos o cumprimento desta lógica. Mas também quando prometemos levianamente coisas que estão bem para lá da nossa capacidade de garantia, sendo o meu ex-libris preferido deste paradigma os filmes de Hollywood em que o herói, prestes a partir para a guerra, consola a noiva chorosa com um: "prometo-te que volto são e salvo".

É ainda curioso analisar: o que nos inibe de renegociar? O que nos leva a saber perfeitamente que vamos chegar atrasados e não avisar? Ou termos a nossa parte do projeto atrasada e preferir resolver pela calada com duas noitadas extra? Poder-se-ia escrever um livro sobre o tema. Num resumo abusivo, diria que não sentimos adequado renegociar. É ser menos. No mínimo, é perder a chance de se ser incrível. Ora, quando prometemos a mais, falhamos; e então prometemos ainda mais impossíveis para compensar, num eterno ciclo vicioso e consequente indomável sentimento de culpa.

Da mesma forma, quando caímos na armadilha de gerir expectativas - que residem na cabeça dos outros, fora da nossa área de controlo -, em vez de gerirmos compromissos - que podemos garantir ou negociar -, minamos os alicerces mais profundos da nossa tranquilidade: a certeza de estarmos a cumprir o que prometemos.

BROKEN PROMISES

We live in a universe full of randomness and unforeseens. A part of this world is inside our area of control: for instance, you chose what you’re wearing today. Another part, isn’t – you weren’t called on this fantastic late October weather, nor if your chief would come to work on a good or bad mood.

The border is flexible: someone with an highly controlling profile will be permanently trying to conquer more and more area of influence, in the same way that a Tibetan monk will grow acceptance, reducing it. And from this elementary distinction, comes a structural reflexion about the notion of Commitement.

Imagine you scheduled a coffee with a friend at 14h30. An unexpected waiting line at the bank delays you. Any system problem. When it’s finally your turn it’s 14h00 you realize that it will be difficult, if even possible, to arrive on time to your commitment. In the best case scenario, you’ll arrive at 14h40, maybe 14h50. What do you do?

Hipothesis 1: You call your friend immediately to notify him, asking if it’s reasonable to reschedule to 14h45.

Hipothesis 2: You only call him at 14h30, saying you’re on your way, running 5 minutes late (therefore, lying).

Hipothesis 3: You don’t call and arrive at 14h45, super stressed, making all kind of excuses, explaining that something totally unexpected made you arrive late.

Which hipothesis shows effective zeal for the made promise?

This question is particularly impactful in high performance teams, where the “trust” and “reliability” foundations are unavoidable values. No one questions that there are uncontrollable variables, but being responsible requires above all things the immediate renegotiation when one of that variables endangers a promise so that everyone can repositionate accordingly, using their time better, or even help if it’s needed. Project managing is one of the domains that better knows the benefits of impeccable commitment: everyone must notify BEFORE failing, as soon as they agknowledge that possibility, not with the crisis already settled.

I think we are culturally skewing, even maybe emptying the concept of Commitment. On the one hand, when we neglect the compliance of this logic. On the other when we lightly promise things that are way beyond our ensurance ability, my favorite ex-libris of this paradigm being Hollywood movies where the hero, about to go to war, comforts the tearful bride with a: "I promise I'll be back safe and sound."

It’s also curious to analyse: what inhibits us to renegotiate? What leads us to know we are going to be late and not warn others? Or having our part of the project delayed and prefer to solve it in silence with two extra work nights? A book could be written on this issue. In an abusive summary, I would say we don’t feel it’s appropriate to renegotiate. It’s being less. At least, it’s losing the chance of being awesome. Well, when we promise more than we can deliver, we fail; and then we promise even more impossibles to compensate, in an eternal vicious cycle and consequent untamable guilt feeling.

In the same way, when we fall into the trap of managing expectations – that live in other peoples’ heads, out of our area of control -, instead of managing commitment – which we can ensure or renegotiate -, we undermine the more profound foundations of our tranquility: the certainty of complying with what we have promised.